The Cuban Missile Crisis is a generational touchstone for those who grew up in America during the 1960’s. In addition to the “duck-and-cover” atomic bomb drills, many school districts issued identification necklaces – dog tags, they were called. I was fascinated, and felt it was my patriotic duty to wear them like advised, though I didn’t understand how they were supposed to protect us. If I asked my parents, I don’t remember their answer. It was years before it struck me that their only purpose was to identify my maimed or dead body and help with an accurate mass casualty statistic. They were tangible evidence of how concerned everyone was about Russian missiles based in Cuba, and potential nuclear annihilation.

I grew up in San Antonio, Texas, which we were told was in the first round of targets. This made sense given our proximity to Cuba and the six active military bases in town. My father was a civil service foreman over aircraft machinists at Kelly Air Force Base and was on high alert for weeks, going in on weekends for emergency preparations, and required to stay close to the home telephone day and night for a few weeks. The world globe we had at school was no longer just a fun object to spin around and daydream about – it showed how close Cuba was! My friends and I spent recesses parroting what we heard at home, amping up each other’s fears. Fridays at noon the air raid sirens sounded, and I clutched my dog tags like a rosary. I don’t remember being as worried about the death and destruction of bombing as I was about the possibility that I might not be with my parents when it happened. I hated for Dad to go off to work, and didn’t want to leave Mom for school in the mornings, even though we lived next door to my elementary school. I have learned that most Americans of my generation believed that their city or region was in the “top ten” of Castro/Khrushchev’s target list. We have a shared remembrance of the intense anxiety of those weeks in October of 1962.

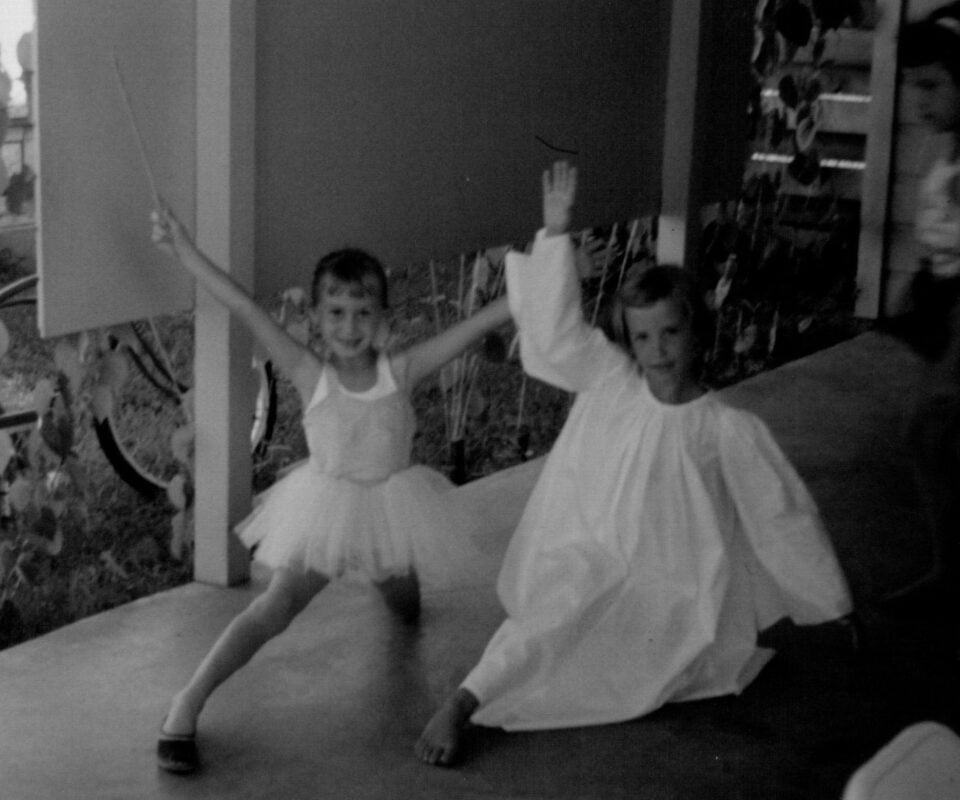

Despite the worries of the Cold War, my childhood was spent in the safety and security of a stable and happy family. My parents were hard working, but also fun and affectionate. Hugging and handholding were natural until, of course, I became a teenager. My parents loved to dance, and there were many occasions when all of us – parents, friends, aunts, uncles, cousins – were together at events that featured live bands, big dance floors, tubs of freshly made tamales and beer on tap. We learned to dance at an early age when it was still alright to be silly and not self-conscious.

“All go and do-si-do, get up and do the Cotton-eyed Joe!” the band leader would say at such an event and everybody would get up and do one of the original “line” dances. There would be German- and Mexican-influenced numbers as well, featuring accordions and mariachis. We learned the Texas two-step, the polka and later, swing and rock n’ roll.

We upscaled from a tiny post-war 2 bedroom, 1 bath house to a new 3 bedroom, 2 bath house about ten minutes aw ay, still in south San Antonio, just as I ended the first grade. We were still only a few minutes from Grandma and Grandpa’s home and most of our friends. My father built a second garage out back to house tools of his trade and the Sweet Sue, a fiberglass fishing boat he built from a kit. Most houses in the neighborhood included kids my age . We roller skated, biked, dressed up in costumes and “played pretend” in the earlier years and then flirted, argued or avoided each other later in high school. We had endless games of chase and hide-and-seek. Once it was too hot or too dark to play outside, we retired to someone’s living room to watch our favorite TV shows like “Shock” and “Tarzan” or Rod Sterling with the original “The Twilight Zone.”

ay, still in south San Antonio, just as I ended the first grade. We were still only a few minutes from Grandma and Grandpa’s home and most of our friends. My father built a second garage out back to house tools of his trade and the Sweet Sue, a fiberglass fishing boat he built from a kit. Most houses in the neighborhood included kids my age . We roller skated, biked, dressed up in costumes and “played pretend” in the earlier years and then flirted, argued or avoided each other later in high school. We had endless games of chase and hide-and-seek. Once it was too hot or too dark to play outside, we retired to someone’s living room to watch our favorite TV shows like “Shock” and “Tarzan” or Rod Sterling with the original “The Twilight Zone.”

When I was in Junior High, my dad bought a used slate pool table straight out of a local pool hall, and fitted it with a removable ping-pong table he made from plywood. The pool/ping-pong table was installed in the second garage. I assume my father envisioned friends and family enjoying game nights in the garage, to complement the badminton and croquet we enjoyed in the back yard, and indeed, that happened. We had rousing competitions and much fun was had. I don’t think he envisioned what a boy-magnet it was. While Mom and Dad were at work during the long summer days, I held my own at both pool and ping-pong while honing my flirting skills.

I remember being in the garage on a scorching summer day, playing pool with a couple of friends, including Dale, a boy I had a crush on. We were playing 8-ball and when I leaned over the table to line up a bank shot I felt the odd sensation of wetness and warmth between my legs. I missed the shot, badly, and made an excuse before running inside the house and to the bathroom. I had an inkling about what might be going on but was still shocked to see blood on my panties, on my shorts and in the toilet. A lot of blood. Not some dainty scraped knee kind of blood, but actual dripping blood. No amount of mother-daughter talks and 7th grade health education prepares you for that moment. Mom was at work, but I found the box of Kotex sanitary napkins we had organized in my closet and figured out the mysterious workings of the sanitary belt and how to hook the napkin into place.

“Are you kidding?” I remember thinking. “Its like I’m wearing a diaper!” I put on clean underpants and shorts but the pad was bulky and awkward feeling.

“Hey Susie, are you finishing the game, or what?” Dale yelled from the garage out back.

“I’ll be there in a minute!” I said, and tried to gain my composure, checking my appearance in the mirror from every angle. I went outside to finish the game, red in the face and sweating, hoping they didn’t notice I suddenly had on different shorts, and certain that the words “STARTED HER PERIOD” must be plastered across my forehead. The guys didn’t seem to notice anything, and I made some excuse to get them to leave as soon as the game was over.

Inside the house, I laid on my bed and thought about how quickly life could change. I was anxious to talk to Mom, and suddenly knew I would feel shy in front of my dad. It was a new day.